Year 9 Future Ready Programme Launches

In February, five Aspirations Academies were involved in the Year 9 Future Ready Programme, delivered by Speakers...

Read more Year 9 Future Ready Programme Launches

Sir Ian Livingstone begins with a question. “Are you a gamer?” he asks. I am, I reply.

I am confident this is the desired answer, as well as the truthful one. We are in the kitchen of his large house in Barnes, south-west London, where he is posing for a photograph with a large model statue of a dragon and the original copies of Warhammer and Dungeons & Dragons, the games he gave to Britain. On the way in, I snuck a peek at his study, where he tells me he has more than 1,500 board games, along with video games, copies of the more than 20 million books he has sold, and two life-size models of Lara Croft, the heroine of the Tomb Raider games, which Livingstone also helped give to the world.

“Oh good,” he says. “It makes things much easier if you’re into games.”

Livingstone, who was knighted in January’s New Year’s Honours, and received his award today, Tuesday November 8, from the Princess Royal, has spent the best part of 50 years telling the world that games are the future, being told that they are not, and then being proven triumphantly correct. At 72, he has the patient but wary manner of a man who has been burnt by the press before. His games have been accused of destroying children’s attention spans, or harming literacy, or of encouraging violence, or outright moral degeneracy. These criticisms have never withstood scrutiny. His games, meanwhile, have beaten off all comers.

Ian Livingstone receiving his knighthood from the Princess Royal at Windsor Castle CREDIT: Jonathan Brady/PA

In 1975, he and a couple of school friends, Steve Jackson and John Peake, were living in a flat in Shepherd’s Bush, west London. They were doing dull, badly paid day jobs, so stayed in a lot in the evening to play games. “We always thought it would be nice if there was more of a gaming community,” he says. They started a newsletter, Owl and Weasel, and a mail-order business called Games Workshop, through which they sold homemade backgammon boards and other games.

One of their newsletters found its way to Gary Gygax, the famous American game designer and co-creator of Dungeons & Dragons. They went over to see him and managed to secure exclusive UK distribution rights to his nascent role-playing game. “He must have wondered who these hippies were. We had long hair and bohemian-looking clothes. But we were the only Brits [interested], so he had no choice.”

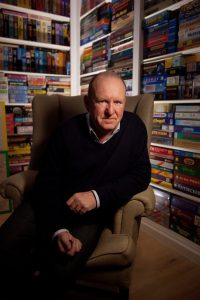

Ian Livingstone CBE, author and entrepreneur. Photographed in London.

With the help of Dungeons & Dragons, but without investment – no bank manager would touch it – Games Workshop started to grow, hand to mouth and cheque to cheque. In 1977, they started publishing a magazine, White Dwarf, which is still in circulation today, and, in 1978, they opened a shop – in Hammersmith, west London.

Part of Games Workshop’s appeal to fans was its immersive nature. Customers did not just come to the shop, buy a few toys and go home – they stayed and played. And, as the chain expanded, Livingstone and his partners prioritised that sense of community.

“We didn’t hire traditional retailers to work in the shops, we hired people like us,” Livingstone says. “They might have looked like Visigoths but they were hugely enthusiastic, and knowledgeable. So they would explain with passion how to play a game, how to paint a miniature [model]. That enthusiasm rubbed off on anyone who walked in through the doors.”

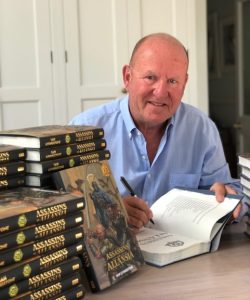

Sir Ian Livingstone signing his new Fighting Fantasy book

Through its publishing arm, Games Workshop also published a new fantasy role-playing game called Warhammer, originally a boxed set of three black-and-white books containing the game’s rules, lists of creatures and recipes for potions and spells. The first such game designed to be played with its own specific range of miniatures, Warhammer quickly gained popularity, and with an exclusive licence to manufacture the miniatures, Games Workshop reaped the benefits. Customers bought, painted and assembled armies of models in one of any number of races, including men, elves, dwarves, lizardmen, orcs and goblins, and then did battle. Warhammer 40,000, a sequel, is still one of the most popular miniature wargames in the world.

Now Livingstone has written a book, Dice Men, about the early years of Games Workshop. An entertaining and very British story, it contains endearingly analogue tales about customers and products being posted to and fro.

The book takes the story up to 1992, when Livingstone and his pals sold out, but the company has continued to grow. At the time of writing, Games Workshop is a globe-spanning empire with a market capitalisation of more than £2bn. There is gold in them orcs and elves.

“Some might say we sold a little bit early,” Livingstone laughs. “But no regrets.”

He is certainly not short of a penny or two. Alongside Games Workshop, Livingstone and Jackson are also the inventors of Fighting Fantasy – a choose-your-own-adventure book series for children which began in 1982 and has, to date, sold more than 20 million copies.

Fighting Fantasy was Livingstone’s first brush with moral panic.

“The books were criticised massively at the beginning,” he says. “The Evangelical Alliance published an eight-page warning saying if you read them you were bound to get possessed by the devil. A vicar in the suburbs got the congregation to burn the books. But over time, teachers realised these were good. They were good for reluctant readers, those with a short attention span. And they developed critical thinking, problem solving. They encouraged creative writing and art.”

The debate certainly didn’t stop readers buying the books. “Playground power was the viral spread of its day,” Livingstone says. “The only publicity we got was negative, but children were enjoying reading. If you start them off reading Shakespeare, you’ll put them off for life. Let them read Shakespeare as and when they’re ready. Fighting Fantasy got a generation of children reading.”

The debate certainly didn’t stop readers buying the books. “Playground power was the viral spread of its day,” Livingstone says. “The only publicity we got was negative, but children were enjoying reading. If you start them off reading Shakespeare, you’ll put them off for life. Let them read Shakespeare as and when they’re ready. Fighting Fantasy got a generation of children reading.”

Sir Ian livingstone pictured in his Games Room

By the 1990s, video games were gaining more of a hold and Livingstone, now a director at games publisher Eidos, bought some of the company’s biggest hits, chief among them Tomb Raider, which was released in October 1996. The first game sold 7 million copies and spawned a string of sequels and two Hollywood films starring Angelina Jolie. “She was amazing,” says Livingstone, clearly still somewhat surprised that his working life brought him into her orbit. “Not just as an actress – she had this incredible presence and intelligence.”

He is a passionate believer in the benefits of gaming. “Cognitively, when you play games, you’re problem solving, learning intuitively,” he says. They also allow you to fail in a “safe environment”, he says, in contrast to exams. “An examination is a brief moment where, if you get it right, you’re seen as able; if you get it wrong, you’re seen as less able. An exam creates a feeling of failure early on.”

He himself was “rubbish” at school, he says, and has a great deal of sympathy for people who love learning but are not academic.

“They’re doing a lot of their learning from YouTube and other ways of learning. When you’re on a plane, would you prefer the pilot had learned by reading a book, or on a simulator?”

Today, Livingstone’s work is embedded in British culture. Earlier this year, the Foreign Secretary James Cleverly admitted to being a fan of Warhammer. Superman actor Henry Cavill has said he finds painting the miniatures therapeutic. And, as Livingstone points out, aspects of gaming can be found everywhere, from artificial intelligence to dating apps.

In short, we are all gamers now – just as Ian Livingstone knew we would be.

Dice Men: The Origin Story of Games Workshop by Ian Livingstone with Steve Jackson is published by Unbound on Tuesday November 8

In February, five Aspirations Academies were involved in the Year 9 Future Ready Programme, delivered by Speakers...

Read more Year 9 Future Ready Programme LaunchesThe first Aspirations Employability Diploma final of 2025 marked a significant milestone in the academic year, bringing...

Read more AAT Celebrates First Aspirations Employability Diploma Final of 2025The Diversity and Inclusion in STEM report acknowledges the lifelong benefits of STEM-related skills. It notes that opportunities...

Read more Dr Jeffery Quaye OBE: The next government must shift our anti-maths culture